“The Alice” in those days was an outpost of wooden houses and corrugated iron surrounded by the distinctive ochre hills of the red centre of Australia. It had no more than 5-600 people living there but there will still signs of when it had housed more than 200,000 people during the war including military camps and the refugees who fled the bombing of Darwin.

It hadn’t occurred to me to check the bus timetable to go further north and I soon learned the error of my ways as I had to wait for a week for the next bus. I was stuck in my hotel which was rough but would have been ok if one of the local drunks hadn’t fallen down a lift shaft that hadn’t been finished. He landed right next to my room which adjoined the stairway. It wasn’t particularly pretty and gave me an aversion to my room. But unless I intended to drink myself from 11am to midnight there were few opportunities for recreational pursuits.

Luckily I ended up meeting my father’s ex-boss while I was there, Don Newland of Newland & Tarlton. He had retired to the Northern Territory. I’m assuming it was where he was from originally as I can’t imagine any other reason that would draw someone to retire there. We spend a night yarning in the pub during the course of which he recommended that I kick my heels for the rest of the week at a place called “Bond Springs” which wasn’t too far from Alice Springs and was owned by a mate of his. I camped there two nights and during that time we had to get a “killer” (a beast to be killed for the station’s meat supplies). It was a good introduction to the sheer size of Australia’s outback. We had to travel 12 miles before we even saw a beast!

I got back to Alice Springs in time to board my bus to Aileron, which was no more than a pub on the side of the road somewhere in the empty landscape between Alice Springs and Darwin. I stayed the night in the pub (I was becoming familiar with rough Australian pubs) and the next morning was welcomed with the plume of dust that heralded the arrival of the truck from Napperby Station. It was driven by the only white man on the station, Monty Scobie. His father, Alec Scobie, had been a champion whip maker (even now one of his plaited leather stock whips can sell for about $8000) and Monty had inherited a lot of his father’s skills. He made me a normal horsehair whip for my stay which I treasured for many years. Monty was a good bloke- slow of speech but with a quick sense of humour.

A couple of hours later we arrived at the station. Napperby was a big wild place. Even the aborigines were wild. They couldn’t speak English. They had a few words of pigeon but mostly it was sign language. There was a tribe of about 200 of them whose camp was right next to the station homestead. They were supplied with tobacco, tea, sugar, jam, maize meal and rice but mostly they still lived on what they got from the bush.

The place was about 4000 square miles and Monty was the care-taker. There were also two half-caste aboriginals who had been born on the place, the results of liasions between a previous owner the aboriginal women. They were the bosses of the mustering teams and each team consisted of about 20 young male riders from the tribe.

The station homestead was a traditional, four-roomed wooden house with a verandah. I use the word verandah in its most liberal sense since this one was peppered with charred holes- evidence that the aboriginals had a blase attitude towards fire risk and insisted on building their campfires there when they chose to camp away from the main settlement.

A couple of the aboriginal women were supposed to look after the house and no doubt they did so according to their own standards. They failed to be bothered by needless concerns with dust and dirt and stale food that have been drilled into Europeans over the years and so the rooms had a pungent odour that clung to the walls and floors and which my nostrils could not cope with.

After one gasping, suffocating night in one of the rooms Monty suggested with a wry smile that I might be more comfortable on the verandah and that is where I lived for the next three months, being careful not to roll too much in my swag in case I fell through the floorboards.

When I arrived it was soon clear that my expectation of being shown around the place and offering to help with a few jobs was not going to be the case. In fact I was considered very fortuitous, free labour. They were just about to start a muster and on the day I arrived they were dishing out the gear- red or blue shirts, according to which mustering team you were in, light coloured trousers, boots and a 10-gallon akubra hat for each man.

They had had to muster because the owner, a playboy by all accounts, was on a trip around Europe and had wired to say he had run out of money. Could we please gather and rail 600 head of cattle and sell them in Adelaide and send him the money so he could continue his tour of the capital cities.

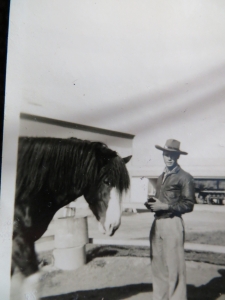

The first thing we had to do was get the horses ready, most of whom were brumbies. Before I had got there they had had an attack of Birdsville Disease which had wiped out about 200 of their 300 horses. So they’d bought horses, at some expense, from their neighbours who had gathered up all the brumbies on the place and herded them into the Napperby yards. Now we had a week to select our horses and break them in.

Monty was pretty good to me, he selected my horses and made sure I had a good night horse with a few years experience. But I also had three brumbies. I’d never broken a horse in my life and I soon learned that the aborigines did it the old-fashioned way. Gentle the horse just enough to put a bridle and saddle on, jump on and hang on for dear life.

I was really quite surprised that most of the horses did come to hand after this. It taught me that to break-in horses the most important thing is to have the right frame of mind and to be able to communicate with the horse. All the aborigines seemed to be able to do this and I tried to emulate them. I don’t think I did too badly, certainly I was never thrown, at least not in that initial week.

Two of mine settled down after a week but one we had to bush because he wouldn’t calm down. His mistake. They chucked two 10-gallon water bags on him and let him buck himself to exhaustion. Then he was put on a leading rein and became a packhorse. Everything had to be carried on horse-back- there wasn’t even a wagon on the place.

We held the horses in a mob as we went out to our first camp where they were hobbled and let go every night then brought in by a ranger in the morning. Once we started collecting cattle we had to take shifts on riding round the cattle through the night. In total we were out on muster for about six weeks. I have to admit I found it pretty hard. Even thought I’d ridden every day while at FOB Wilson’s it was nothing compared to being in the saddle for hour after hour surrounded by swirling red dust and shimmering heat.

We started off with two tins of jam, golden syrup and tea and sugar. We had flour so we could make damper every day and I had also smuggled from the homestead pantry three tins of peaches, one tin of apricots and two tins of plum jam. All of which I consumed in the first week.

Then I was forced onto the beef and damper. We had fresh beef for the first few days and when it started turning bad we put salt on it and kept eating until it was finished. Then we killed the next beast.

By the time I’d been out there three or four weeks I started hallucinating about tinned and fresh fruit. I’d never eaten beef before I got to the Territory and now I was living on the damn stuff. At home I only ever ate chicken or fish. It wasn’t that I didn’t like the taste of red meat but I didn’t like the endless chewing it required- I assume my teeth have always been a bit weak due to my infant lactose intolerance and subsequent lack of calcium.

Now, not only was I eating beef morning, noon and night but I was also having to drink pretty dirty water. I’d drunk a bit of dirty water in Kenya- if you were out hunting and found a pond or something- but this stuff was on a different scale. We had to dig it out of a dry river bed where 500 cattle had been camping. I’m pretty sure that the fluid we dug up was probably about 90% cow piss. We’d try and convince ourselves that the salty taste was simply the salt in the ground but I was never convinced. I started trying to limit how much water I drank and ended up getting quite dehydrated.

But I must have been healthy. After we’d been out for three or four weeks my horse unexpectedly reared up and backed into a dead mulga tree causing one of the branches to slam right through my shoulder. The horse fell away from underneath me and I was left hanging about three foot off the ground, helplessy pinned by the now bloodied stake of wood.

The aboriginals thought it was the biggest bloody joke since Christmas. They were rolling about on the ground laughing, deaf to my swearing and cursing. Eventually they came and tried to lift me off the tree but I was really stuck. They looked for another way and tried to break the branch off from the tree by half of them hanging onto me and the other half onto the branch. That yielded little result either, other than my yells reaching a pitch that any good soprano would be proud to achieve.

Eventually they got the axe, which we used to cut kindling up and which was as blunt as hell, and started chopping. My god, I swore blue murder. After they got it down they then wedged me against a couple of them and pulled. It came out eventually but there were still quite a few splinters and debris left in the wound not to mention a great deal of shredded nerves all throughout my body. There was no clean water so I peed in the jerry can and bathed it in urine. I managed to get most of the sticky bits out that I could find and then I wrapped it up with my spare shirt because it was the only thing I could find that was reasonably clean.

I left it for three days before I peeled it off to take a look at it and do you know, it was damn near healed and not a sign of infection- despite the fact Mulga timber has a bad reputation for infection. After seven or eight days it was scarred. Funnily enough I’d often noticed that Africans could heal almost overnight from massive wounds without any medicine so maybe there’s something about the diet or being outdoors- I don’t know. Either way I was very relieved although it remained painful and weak for quite some time after that.

At the end of three weeks we had about 6-700 cattle and we needed to start castrating and ear-marking. One rider would ride into the herd on the bronco horse- a big heavy draft horse with a special saddle- lasso the beast and drag it back out of the herd by the neck. We had a rough makeshift area with two lines of stakes in the ground and two panels about 12ft apart to make a bit of a corral. We would put ropes on the front or back legs and pull until the beast fell down. They tend to go down fairly hard doing it this way, and then we’d all get in there- one to dehorn, one to castrate, one to ear-mark, another to administer jabs. It was really hard work and every beast had to be handled this way. By the time we had finished both we, the whole herd and the bronco horse would literally be covered in blood. I thought it was pretty cruel and I reckon we probably lost anything up to 30% of the beasts we marked simply through heat, flies and dust doing their work on the wounds.

Still we managed to finish the muster and send the required number of beasts off to market.

A month or so after we got back off muster Monty took me to the annual meeting of the Barrow Creek Race Club which was always held at Aileron. There must have been about 3-400 people there- ringers, aboriginals, station owners- anyone who was anyone in the local district. I remember almost nothing of the racing itself as we were all hopelessly drunk for the entire three days it was on.

In our drunken halo some bright spark suggested we all play water polo in a billabong about a mile away from the meet. Everyone agreed this was an excellent idea and we all drove, walked, rode out there and proceeded to strip off. Everyone played, men in their underpants or riding britches, women in their bras and pants or even fully clothed. It was very funny and I was enjoying it immensely until they decided to start throwing around this big watermelon as a ball instead. My shoulders were in pretty bad shape- one having been dislocated recently and the other still healing from the mulga accident. This bloody melon slammed into the shoulder that had been dislocated and promptly popped it back out.

This was not the kind of company to deal with a medical incident, in fact any kind of medical incident. One ringer, still pretty drunk, said: “Oh I’ve dealt with this in cattle, you need to pull hell out of it and slam it back in.” Which he proceeded to demonstrate with gusto.

“No, no, no,” said another “You’re doing it all wrong, let me have a go.” He knelt on my chest and gave it a few tugs. He seemed mystified at his lack of success.

Another four, all highly inebriated, shoved him out of the way and kindly insisted they would have me “right as rain” in no time. As a group they embarked on various pushing, pulling, thumping and stomping techniques. By this time all I could do was to give the faintest cry of pain as I devoutly hoped the ground would soon open up and swallow me whole.

Finally a young bloke appeared. I’d not seen him the previous days but he must have been a trainee doctor or something because he manipulated it in the proper way and the shoulder went back in quite easily but by that time I had almost passed out with the pain.

When I got back to Adelaide they told me some of the shoulder cup had actually torn away and so I had an operation to repair it and was in hospital for about 10 days.

But there’s something to be said for the healing powers of the young. Within three days of the race meeting I was able to use my shoulder enough that I could drive a cattle truck from Aileron down to Alice Springs (about 300km).

This was my first experience of night driving in the Australian outback and it scared the hell out of me. This wide stretch of red dirt with white posts every 50 yards that just stretched on and on and on- no bends, no hills, nothing to break the monotony. I started falling asleep at the wheel and as I tried to keep my eyes open the white posts started turning into non-existent cattle jumping into the road with me swerving wildly to avoid them. After it happened three times I started seeing the advantages of having a nap before I continued with the drive.

Finally my three months were up. I caught the bus back to Adelaide to start college.