We first-years boarded in the main building of the college that had been built when the college was first established. It housed a maximum of 30 students and it only had one toilet. More often then not you would be forced to go out the back door to a row of outdoor toilets which had no roof and an open drain taking the stuff God only knows where. It was a test of how badly you needed to go, particularly in winter or when it was raining. And since the fumes caused severe retching and gagging- you certainly didn’t linger.

As second years we used the same toilets but our digs were a block of 31 individual units with ceilings no more than 7ft high, concrete floors, a single bed and an open verandah that circulated the building.

And as third years we moved again to some ex-army huts which had three to four rooms to each. They weren’t lined or sealed and there was nothing much in the way of insulation. But they did have their own set of toilets and wash units, although, again, outside. The showers consisted of a concrete floor with a sheet of corrugated iron circling it. Whoever built it obviously decided it wasn’t worth the expense of another sheet of tin and so there was a large gap at the bottom and the top which meant it was draughty whichever way the wind blew.

In winter these were the coldest bloody huts I’d ever been in. The students would all put copper pennies across the 15-amp fuses to stop them blowing when too many heaters were connected. We would do this until all the wires between the huts were literally glowing. The college provided one heater per room but most of the students already had (or rapidly aquired) a heater of their own. Unfortunately, even with the penny trick, it couldn’t usually take more than two or three heaters so we had to take turns as to who missed out on having the heater in their room that day.

We also had a tiny little cooker which we had to light and feed with firewood. It had a hot-top but you would actually have to sit on top of it to get any warmth from it. It’s main purpose was to heat the water for the showers. We had one bloke in our group who would get up at 5am every day without fuss and light the cookbox. He’d get us up an hour earlier than the others and keep the fire going so we all had a hot shower and then he would let it go out. Because even if the water was absolutely boiling, the draft in those showers was such that you would still be cold but at least your teeth wouldn’t actually be chattering nor your skin a curious shade of blue.

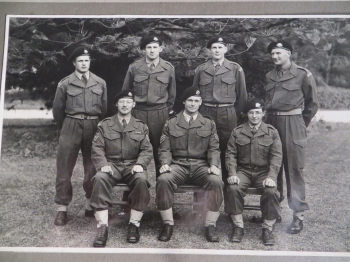

As first years we were encouraged to join the Citizen Military Forces or what is now known as the Army Reserve in Australia. If you wanted to go into the military following college then your time with the CMF counted. I had no interest in a military career but I knew firsthand the powerful appeal of a military uniform on the ladies so I signed up in my first week. I took two further courses – one in radio communication and one on tank gunnery. I was soon promoted to corporal and in the uniform I looked pretty bloody smart I can tell you. I took every opportunity to wear the uniform and its success with the ladies was as I predicted. I soon earned my nickname “Buck” Sands.

Unfortunately, I think this started years of chronic deafness. I was usually in the turret of the armoured car, directing the gunner underneath. We didn’t have any ear-muffs and so my ears took a drubbing as the huge gun blasted just 3-4 foot away. I also became captain of the rifle club at University and even then we were using big bore rifles that packed an audio punch. At inter-college shooting competitions there were eight .303’s exploding every 20 seconds. I was often pretty deaf at the end of gunnery courses or rifle competitions but it usually came back within a couple of days.

By the time I finished my second year course I was promoted to Sergeant in the tank regiment. We had to go on troop manouvres around the countryside in small units. It was pretty hilly countryside, just behind the Barossa Valley. On the second day we hit a muddy valley. I was in the rear tank of Number One Squadron and the leader had the front tank. The leader got his tank through but in doing so had churned up the ground so much that the second tank sank like a stone, right up to its belly. The leader directed that a 20 yard wire rope be used to pull out the stranded tank but it didn’t shift an inch. So he shifted his tank to a fresh spot to try a different angle and managed to get his own tank firmly bogged as well.

I had been watching all this with mounting frustration and finally got out of my tank and took charge. We had another three tanks not bogged so I got two of them on a split rope pulley and anchored the stranded tank to another tank sideways so essentially we had the pulling capacity of four tanks to a fixed point. It worked like a dream and we got both tanks out without hassle. That was probably my biggest military moment of triumph. The possession of a little mechanical engineering knowledge got me mentioned in dispatches, so I was well pleased.

It was also during my second year at college that I received the news that my brother Jack had died. While at the University of Oxford on his Rhode Scholarship he had joined an aerobatic flying display team and while practicing a complicated manouvre he had dived through a cloud and collided with a small civilian aircraft on the other side. Both pilots were killed.

Although we had never been terribly close Jack was probably the brother I liked the best. He was probably the brother everyone liked the best- he was gifted with both looks, athletic ability and an open-hearted sociability that never failed to draw people to him. It seemed such a terrible tragedy that he should have been struck down so early in a life full of such promise. But so it seems whenever someone young dies I suppose.

His death came as a horrible shock and for the first time I really felt the distance between Australia and Africa. I was grateful then when Margaret Patterson wrote me a touching and heart-felt letter of condolence.

Her sister Ann was ostensibly still my girlfriend at this time (at least it was her photo I had on my wall in Roseworthy) but she probably only wrote me two letters in the four years I was in Australia. But Jack’s death prompted a regular exchange of letters with Margaret who was a talented and entertaining writer. Margaret was actually in London during this period. After inheriting money following the death of her grandmother she had decided to follow her dream of writing and acting on the stage and was attending the Guildhall School of Drama and Music.

I was regaled on stories of luvvies and drama-folk which made me chuckle and it wasn’t long before Ann’s picture had been replaced by Margaret’s in my room at college.